Methods

What should a non-specialist know in order to use this archive?

What kinds of stories can we tell with linguistic evidence?

How do we know what words meant if they weren’t written down?

This online material offers an initial orientation for the non-specialist to the methods undergirding the production and analysis of data used in “Sounding the African Atlantic,” published in the October 2021 issue of the William & Mary Quarterly. The data for that article can be accessed through the Omohundro Institute’s OIReader. Taken together, the explanation of methods offered here and the supplementary data published with the OIReader serve as a starting point for scholars interested in teaching and learning Atlantic history through the archives of comparative historical linguistic. To that end, this site also offers materials to facilitate the use of the “primary source data” published with the OIReader to teach the history of Atlantic slavery or African American intellectual history in the undergraduate and graduate classroom.[1]

[1] Thanks to Koen Bostoen and the research team at BantUGent, Chelsea Berry, and Marcos de Almeida for sharing materials and suggestions.

1

What should a non-specialist know to understand this archive and assess its use?

To understand how historians use linguistic evidence as historical evidence, non-specialists need to understand the criteria by which we identify the origins and circulation of words and analyze contests over their durable and changing meanings. In other words, they must familiarize themselves with the methods of comparative historical linguistics.

Historians who use linguistic evidence assume that words are historical artifacts attesting to the existence of the idea or object to which they refer. Through the methods of comparative historical linguistics, the histories of words can be reconstructed even when documentation of words’ use is slim or absent in the historical record. While recognizing the fluidity and, indeed, heuristic qualities of ‘language’ as a unit of analysis, the subfield of historical linguistics conceptualizes such change, in part, phylogenetically—that is, through the metaphor of biological descent—but also through the dynamics of contact and interaction. In this understanding, languages change over time as speakers in different regions adopt new words, adapt syntax or morphology to express new ways of thinking (or forget irrelevant ones), change their pronunciation, share in the soundscapes and terms of debate of neighbors speaking other languages, and so on. These changes slowly accumulate over centuries or millennia into regional dialects and, eventually, can reach a point whereby dialects of a language once similar enough to enjoy mutual intelligibility are now so different as to constitute distinct forms of speaking—distinct languages. In other words, the ancestral protolanguage has diverged into new languages, which constitute the next generation of the language ‘family’ and will, themselves, be subject to the same process of divergence over time.

By comparing the linguistic features—phonological inventories (sounds), morphemes (meaningful word parts like prefixes, suffixes, etc.), grammatical structures, lexis, and so forth—of languages hypothesized to be related on the basis of their surface similarity, we can determine whether languages’ similarities arise from phylogenesis (ties to a common ancestor) or contact stemming from historical processes like trade, migration, or colonization. Often, similarity arises from both kinds of relationship—genetic and contact-induced—simultaneously; indeed, contact influence can span very long periods. Analysis of the results of comparison yields a classification or phylogeny (like a family tree; see Fig. 1) that serves as a relative chronology of linguistic change usually marked by periods of contact between languages belonging to different families or between different branches of the same family. Importantly, this historical change can be reconstructed in the absence of its historical documentation precisely because it depends on a comparison within groups of genetically and spatially related languages, just as population histories can be reconstructed through modern blood or saliva samples. And like phylogenetic research in molecular biology, reconstructed patterns of linguistic change can be compared to processes and events documented in the traditional archive or in the archaeological record.

| FIGURE 1: Sample Classification Outline Classification of Botatwe Languages |

| Proto-Botatwe (57-71% [100-900]; 64% median [500]) I. Greater Eastern Botatwe (63-74% [500-1000]; 68.5% median [750] a. Central Eastern Botatwe (70-77% [800-1100]; 73/5% median [950] i. Kafue (78-81% [1200-1300]; 79.5% median [1250]) 1. Ila 2. Tonga 3. Sala 4. Lenje ii. Falls (91% [1700]) 1. Toka 2. Leya iii. Lundwe b. Soli II. Western Botatwe (76-81% [1100-1300]; 78.5% median [1200]) a. Zambezi Hook (83% [1400]) i. Shanjo ii. Fwe b. Machili (84-58% [1400-1450]; 84.5% median [1425]) i. Mbalangwe ii. Subiya iii. Totela |

Word histories yield evidence of human histories, even in the absence of documentation of those histories. The historical development of language attributes (phonology, morphology, and so on) teaches us about the historical development of languages and language families, of course, but the histories of words—their invention or inheritance, their exchange between communities speaking different languages but collaborating on shared projects, their multiple, changing and contested meanings—offer insight into the actions, objects, and ideas of languages’ speakers.

In order to reconstruct words’ histories, we must first complete the work of classification described above, including the reconstruction of changing sound systems (diachronic phonology) within language groups. Once the genetic and spatial relationships among extant and extinct languages is understood and the diachronic phonology reconstructed, linguists can reconstruct a word of interest by assessing its form (i.e. its constituent morphology[parts] and phonology [sounds]) within the languages of a genetically or spatially related group. The forms of the attestations of a root word in related languages determines its antiquity—whether it was also present within the different generational nodes or protolanguages (ancestral languages) of the wider language family. These features also tell us which of three historical processes is responsible for the word’s presence in each stage of the language family’s development:

1) borrowing from another language;

2) internal innovation, and, later;

3) inheritance of such loans and innovations.

The pronunciation of an inherited word follows the sound changes that contributed to its differentiation (divergence) from the ancestral language that first innovated it (see Fig. 2). For example, we recognize the antiquity of the root *-dʊ̀- [hyperlink to this root on the teaching side of this website] through its broad distribution within in and beyond Bantu languages as well as by the way its pronunciation adheres to the sound changes that gave rise over time to the languages that use the root today (in this case, *d > l and *d > r). Similarly, a word borrowed in the distant past will exhibit the phonology of its donor language in the period of borrowing but will follow all of the relevant sound changes associated with divergence as it is subsequently inherited by the descendent languages of the initial borrowing language (see Fig. 2). In sum, patterns in phonology are essential to determining which words in languages are related to one another and precisely how they are related, now and in the past. Phonology and morphology are essential to determining the potential source language(s) of words found in historical contexts with very sparse or non-existent written records.

| FIGURE 2: Grimm’s Law Proto-Germanic (PGm) underwent a well-known sound change rule called Grimm’s Law in the first millennium BCE in which Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stop consonants (in English, the stop consonants are t, d, b, p, g, k) shifted to stop and fricative consonants in PGm (*p > f and *d > t in the example below) as part of the process of the divergence of PGm from its immediate ancestor. The word ‘foot’ illustrates Grimm’s law enacted on the first and second consonants of the late PIE *pōd, a variant of the early PIE root *ped-. We can see the sound change easily by comparing attestations of stop consonants in the older PIE form *ped- in another PIE branch familiar to readers, the Romance languages. Further sound changes, such as the voicing of the fricative /f/ (rendered /v/) definitive of Dutch or the loss of the second stop in Iberian languages, attest to the phonological shifts underlying subsequent divergences (of PGm and Proto-Iberian, in these examples). |

| Proto-Indo-European *ped- ‘to walk, to step, to stumble’ and ‘foot’ A variant, *pōd-, developed late in PIE history. Daughter languages inherited one or both variants. |

| *ped- (<Latin pēs gen. pedis <PIE *ped-) Modern French: pied Modern Italisn: piede Modern Spanish: pie Modern Portuguese: pé | *pod- (late var. of PIE *ped-) Old English: fōt Modern English: foot Modern German: fuβ Modern Dutch: voet |

| Knowing the form we would expect the PIE root variants to take in English (and other Germanic languages), we can better identify loanwords into English. We can thus identify ‘fetch’ as an attestation of PIE verbal root *ped- inherited into English (and, in other forms, into other Germanic languages) from PGm because it follows expected sound change rules. A host of other seemingly distinct English terms trace their roots to the PIE root *ped-, often metaphorically through combinations with various morphemes: pessimism, impeach, impair, pedestal, and so forth. Similarly, we can recognize ‘peon’ as a word borrowed into English from an Iberian language that dropped the final stop consonant on the root. Medieval Latin pedonem ‘foot soldier’ derived from PIE *ped- but took the form peón in Spanish in reference to a pedestrian, day laborer, or farm hand (with the connotation of being in service to or indebted to another, in motion as a result of inferior status or of inferior status as a result of being in motion). We might recognize the same underlying concept and (Iberian?) form in the term ‘pioneer’, a loanword into English from French (Middle French: pionnier; Old French paonier). Sources: Campbell 2004:156; Pokorny 1959; Slocum et al., n.d.; Watkins 2000: 62. |

In this way, the phonological changes that differentiated generations of a language family over time can serve much the same purpose as the stratigraphic layers that guide the relative chronology of archaeologists’ excavations, the paleographic conventions that allow historians to recognize in broad terms the period of undated documents, or the chemical composition of paints that allow conservation scientists to authenticate paintings.[1] Phonology is also essential to differentiating languages from one another in the past, much like paleographic conventions and paint or pottery recipes can differ geographically at the same moment in time. As a result, historians using linguistic evidence or assessing its use by others should be wary of those who attribute words to source languages without supplying the underlying phonological and morphological evidence supporting their attribution. However, not all words of interest in a particular region contain sound changes that allow for such analysis; some consonants, vowels and tones are durable in particular subbranches of a language family because those languages have been phonologically conservative. In other circumstances, we don’t yet have enough data from poorly documented languages to fully identify the origins of a term or the precise direction of loaning and convergence, as is partially the case with the homophonic clusters around *-kànd- and *-kánd- [hyperlink to this root on the teaching side of this website].

It is important to remember that Atlanticists already intuitively do this sort of phonological and morphological analysis when they encounter European terms in their archives. Even when they are not fluent in all the relevant languages, historians learn enough of the phonology and morphology of European languages to correctly attribute the terms or documents they encounter to the appropriate languages. For example, historians already know Spanish documents might discuss the ‘artista’ responsible for the illustration in a medical treatise, but French speaking contemporaries would have discussed that person as an ‘artiste’ because las convenciones lingüísticas of Spanish phonology and morphology are distinct from les conventions linguistiques. Historians of the Atlantic and the Americas similarly call to mind cognates, recognizing the relationship between pater, padre, vader, and father and perhaps even the status of ‘père’ as a doublet, despite the fact that these cognates belong to distinct (but distantly related and frequently in contact) language families. The regular sound shift invoked in this example (called ‘Grimm’s Law’) differentiated Germanic languages from other Indo-European languages. The subsequent shift to /v/ (voicing of the fricative) in Dutch are simply part of Atlanticists’ intuitive knowledge, a knowledge acquired through language learning and reading within the field, rather than patterns learned explicitly as formal sound change rules in linguistics research (see Fig. 2). As a result, misattributions of European terms are rare. Indeed, the widespread character of this intuitive linguistic knowledge within the community of historians ensures that any such misattribution is likely to be caught during peer review. This is not yet the case with the many African languages relevant to the history of the Atlantic (extant or extinct), particularly those that did not serve as linguae francae.

Knowledge of derivational processes drawing on the morphology of languages is similarly intuitive to many historians of the Atlantic and the Americas. We know the term ‘hunter’ derives from the term ‘hunt’ and ‘collectivities’ derives from ‘collect’ and not vice versa because we recognize the morphological units in play—the agentive, denominal, and plural suffixes—and we know the rules for their combination with verb roots like ‘hunt’ and ‘collect’. For example, we know that the plural suffix ‘es’ on ‘collectivities’ will always come after (and modify the form of) the ‘-ivity’ suffix that derives the noun ‘collectivities’ from the verb root ‘collect’. We further know that suffix -ivity specifies a noun of quality (a noun for an abstraction or collective), in contrast to the agentive suffix -er that renders ‘hunter’ the agent of the verb root ‘hunt.’ We might also be aware that in French the agentive would be –(l)eur, -(t)euse, -trice, or -iste relating (in some cases as cognates) to Spanish -dor(a), -ero(a), -ista, -ario(a). For example, it is on such morphological grounds that we can recognize in Makandal, the name of famous ‘poisoner’ of mid-18th century Saint Domingue, a deverbative noun—a noun created from a verb with an extensive affix.[2] Recognizing the phonological and morphological form of African words assists us in attributing words to languages and understanding the nuances of their meaning. Further, it allows us to distinguish words derived from the same root word from words that are homophones within and between related (or very distantly related) languages.

The etymologies, changing meanings, local distinctive attestations, and homophones (easily mistaken for cognates) of regional (even continental) word roots are all useful information for historians, but they attest to different processes and, thus, sustain different historical interpretations. Just as an historian needs to know the genre of a document in order to understand how to interpret the historical information embedded within it, we need to be clear about which kind of relationship exists between similar-looking or similar-sounding words with similar—or vastly different—meanings. A confession solicited on the ‘sellette’ in French colonial Louisiana will be contextualized and interpreted differently than an autobiographical account of a runaway slave published by the Boston Anti-Slavery Office. So, too, must the historian recognize different historical information in evidence of different linguistic relationships in the multilingual context of the Atlantic: a false cognate pair circulating in Palmares tells us something different about historical processes than the conservation of a widely-dispersed ancient root with stable form and meaning in initiation chants in late colonial Saint Domingue.

Attention to phonology and morphology is all the more important when sourcing African words because so many of the African languages relevant to Atlantic history were not documented until the 20th and even 21st centuries. Searching for words’ sources in early modern dictionaries alone leads to the incorrect and over-attribution of African words recorded in colonial archives to those languages best documented at the time, skewing our understanding of the many societies involved in Atlantic and American histories. And, indeed, many speakers of languages not documented at the time learned regional languages like Kimbundu. Even within the historical dictionaries and grammars of well-documented African languages, we can identify loanwords from languages that were not documented at the time, reminding us of their influence and relevance for the histories we seek to recover through language evidence. Similarly, polyglots brought words naming the concepts and practices of ‘undocumented’ communities into the Atlantic because they were relevant, even when they did not identify with or belong to the community that invented such words. We can trace the different itineraries of words (and the ambitions, experiences, and values of their diverse users) by comparing the forms and meanings of the words recorded in the archival records of the Americas with the forms and meanings of words in African language groups, whether documented in the Atlantic era or more recently (often through fieldwork, at least in Africanist scholarship).

It is vital to remember that historians trained to work in more traditional Atlantic archives already do this unconsciously for words from European languages because they have a deep, intuitive knowledge of how early modern dialects of the many European languages differed from their modern counterparts and how words changed meanings over time within those languages. The sheer number of African languages and the intensity of Atlantic-era contact and convergence make this more challenging, to be sure. But the numbers of African languages and their patterns of contact also offer a detailed, high-resolution historical linguistic archive for writing the history of the continent and her many diasporas. Importantly, the technical work of classification and phonological and lexical reconstruction has already been completed by specialists in some regions relevant to Atlantic histories.

[1] We might think of these efforts both in terms of the application of methods from materials science to the diachronic assessment of production techniques (as in archaeometry [archaeological science] and conservation science) and in terms of the analysis of the unintentional production of historical material, as often considered in, for example, archaeological analysis of middens or in Carlo Ginzberg’s essay on the ‘Morellian method’ (2013 [1986]: 87-113).

[2] Following Jean and Suzanne Comhaire-Sylvain, David Geggus proposes that Makandal’s name comes from a ‘Kongo’ word for ‘amulet’: ‘makunda’ or ‘mak(w)anda’ (1993: 32-33). Both are unlikely on morphological grounds because they require that a verbal affix be applied to a noun, in contradiction to derivational patterns in Bantu languages. The first is also unlikely on phonological grounds; /a/ and /u/ are rarely mistaken in the language documentation. The second appears to include a glide, suggesting a lost consonant (/b/?) in the CVCV pattern requiring a bridge between vowels, but this glide is not in evidence in Makandal’s name. The latter is a word from KiYombe, a Kikongo language spoken north of the river, inland from the coast. Christina Mobley uses this connection to narrow Makandal’s origins to that region (2015), but the underlying root(s) are far more widespread.

2

What kinds of stories can we tell with linguistic evidence?

A historical linguist determines when a word was produced and by what process as part of the wider effort to understand the history of how languages have changed over time. But the linguistically-minded historian wants to use that information to tell a story about how people understood, debated, and refashioned their worlds. In the Africanist context, historians using these methods alone usually write about early African histories (corresponding to the ancient and medieval periods in Europe). This is, in part, a methodological necessity. Because the documentation of most African languages is fairly recent, we can’t trace changing meanings of words within individual languages in recent centuries through documentation (philology). Instead, we must compare meanings across related languages to seriate the changing meanings of root words at different time periods within the language family tree. When the comparative method is applied in the absence of language documentation over time, the latest period about which a reconstructed word attests datable historical information is the period right before the last divergence, which yields the extant generation of languages. For many parts of Africa, these latest divergences occurred in the middle centuries of the second millennium, between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries (for example, see Fig. 1). From that point forward, the comparative approach can’t yield high resolution diachronic phonological data that would allow us to determine when further linguistic change occurred without dense documentation of languages’ dialects, which is rare in Africa. As a result, Africanist historians who have adopted these methods produce stories within the broad geographical and chronological scales that characterize the change within language families discernable through the comparative method. The historical actors of these stories are the communities of speakers of the modern or ancestral languages (protolanguages) to which particular words can be reconstructed. The scales of time and space and sociability in these histories are larger than those of historians interpreting documentary and oral testimonies of the past, spanning centuries, millennia, and many generations.

A few languages of coastal Africa have some documentation in centuries before the late 19th century, when the documentation of African languages began in earnest (though many remain undocumented today). This documentation allows us to address the chronological limits of the comparative method even as the comparative method allows us to address the geographical limits of the documentation of African languages (which tended to focus on the coasts or trade routes). By leveraging the two archives, we can produce better-dated historical evidence of the contribution of oral African societies to the Atlantic world, even in the absence of any documentation of their ideas, practices, and actions at the time. In this way, the geographical impact of African involvement in the Atlantic world and, particularly, the actions and ideas of Africans that were never recorded for this period become accessible even as linguistic innovation that postdates the last divergence of a language group becomes better datable. Leveraging the two archives, our understanding of the Atlantic extends well beyond the best documented and, therefore, best studied coastal and interior African communities or those individuals, maroon settlements, ritual publics, and families best recorded in colonial archives in the Americas. Finally, the articulation of these two archives also weaves together distinct social scales. Documents record the actions and words of individuals and smaller groups, even when those people are not named or otherwise humanized. The broad linguistic scale of the community of speakers contextualizes individual’s speech as recorded in documents in the wider social world of interlocutors who shared in the project of making and contesting meaningful action in the world through the innovation and conservation of the conceptual terrain named through words spoken (and recorded).

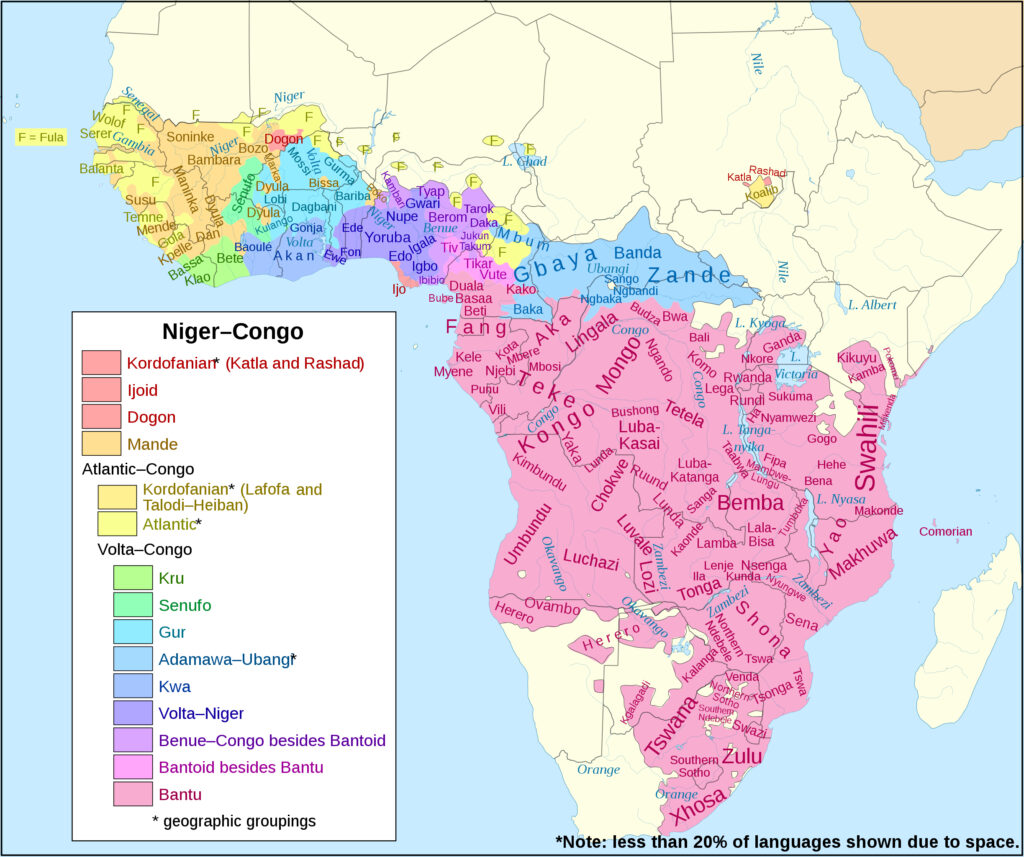

With the comparative historical linguistic method, the histories of words are necessarily contextualized within a multiscalar, multicontextual story that contains the entire history of the development of a language phylum, keeping in our sights the historical significance of earlier and interior continental histories for the Atlantic period. In the case of Niger Congo, that story encompasses most African communities of interest for Atlantic historians (Fig. 3). When words documented in Atlantic archives are studied through the methods of comparative historical linguistics they are not only connected to their source language or region, they are also, necessarily, embedded in the story of any and all cognates yielding the history of a root word or any other morphemes in play. Words’ stories adhere to the web of other attestations of the same root within a language as well as attestations within the relevant geographical and chronological sequences of the language family’s history. Very old roots might encompass the millennia-long and nearly continental scope of the history of the Niger Congo phylum, attesting to both the durability of ancient concepts named as well as the radical change and differentiation needed to conserve relevant parts of such old ideas, particularly as they converged in the early modern Americas from distant parts of the continent (de Luna 2021).[1]

FIGURE 3: Linguistic Map of the Niger-Congo Phylum

In this way, we can begin to recognize additional geographies and temporalities of connection that impacted well-known Atlantic processes. The muliscalar, multicontextual character of linguistic evidence analyzed through comparative historical linguistic methods directly addresses any number of historical problems that have animated the field of Atlantic history. These methods help us recognize what enslaved African men and women could understand of each other. We can know why particular ideas or practices emerged as spaces of collaboration (or disagreement) because we can know the terms of engagement that—quite literally—spoke to men and women from different regions and language backgrounds. We can also know which aspects of the actions and ideas named through such terms could not be recognized—the limits of shared understanding until new tools of communication were worked out (new words, pidgins, creoles, and so forth). Linguistic data analyzed through the methods of comparative historical linguistics helps us better understand pressing questions about the strategies of community-building through nations, marronage, ethnogenesis, and healing in specific historical contexts characterized by particular compositions of enslaved Africans speaking languages with common genetic and contact histories at different time depths. The kind of relationship between African words recorded in the Atlantic and attested on the continent directs its interpretation. The stories words can tell are as varied as their meanings, but, unsurprisingly, the precision of the chronological, geographical, and social scales of those stories depends on words’ phonologies, distributions, semantic ranges, and degree of documentation (including the possibilities for fieldwork).

3

How do we know what the words meant in the past if they weren’t written down?

How can we know what words meant if we don’t have a written record documenting how they were used in the past? After all, in contexts with rich archives, we know that words often carried different connotations in the past than they do at present (a point that lies at the heart of our ability to reconstruct the past from word histories in the first place). But, one might well ask the same question of the ‘meaning’ of the enslaved west central African rebel leader Macaya who wrote to the French republican commissioner stationed in Saint Domingue that he refused to join forces, claiming “I am the subject of three kings: of the King of Congo, master of all the blacks; of the King of France who represents my father; of the King of Spain who represents my mother” (cited in Thornton 1993, 181). After all, scholars have debated what, exactly, Macaya meant in this statement, even if they have not questioned the meaning of individual words. In this sense, no historian (or anthropologist or sociologist or listener) can know exactly what another speaker means, but we take for granted that we can know the full range of meanings a word might take and the appropriate social contexts of use shaping meaning to draw near to what the speaker sought to communicate. It helps, then, to consider what we mean by ‘meaning’, a question that requires us to think about how words mean rather than what they mean (Fleisch 2016: 52).

We might think of meaning as a matter of fact, what linguists call ‘lexical’ meaning. For example, mulimi means ‘farmer’ in a majority of the 500-700 Bantu languages, but it also means ‘prosperous person’ in the Chila language spoken in central Zambia (Fowler 2000:456). Everyone knows what we’re talking about when we are talking about a mulimi. But, the clarity of the meaning ‘farmer’ also stems from the morphology of the word, which is comprised of a noun class prefix indicating the personhood of the noun and an agentive suffix rendering the noun the agent of the action of the underlying verb root. That verb root, *-dɩ̀m-, is a widespread Bantu root naming the act of ‘cultivating’ usually with a hoe (Bastin et al. 2002: 968 [henceforth ‘BLR3’]). We can see, then, that farmer is surely the primary meaning for Chila-speakers even as that act secures the material basis for the secondary meaning of ‘prosperous person,’ a meaning not frequent in other related or neighboring languages. Furthermore, what it means to do the kind of action named *-dɩ̀m- relates to the tools used and the methods needed to prepare fields for different forms of farming, usually with an iron hoe. In the minds of Chila-speakers, prosperous farmers could afford many iron hoes and the wives to use them in acts of *-dɩ̀m-, acts which further ensured the cycle of prosperity. Here, comparison of the evidence for the historical development of farming technology between the linguistic and archaeological records of different regions and times periods can confirm the character of the action named by the reconstructed verb *-dɩ̀m-, which named cultivating or hoeing, the activity undertaken to prepare for cereal agriculture (rather than tuber horticulture practiced in the rainforest belts). In other words, we can confirm the reconstructed meaning through archaeology. The adoption of the same root to name the Pleiades ‘cilimilo’ or ‘cilimila’ in the southern hemisphere or even springtime as ‘cilimo’ (BLR3: 974, 5489; Fowler 2000: 111) tells us when during the annual agricultural calendar the activities of cultivating and hoeing were undertaken, further supporting the root meaning of the verb *-dɩ̀m-. Of course, it is much more difficult to use an independent historical record like archaeology to confirm the meaning of a word naming an idea or belief than a technology or tool, but the success of direct associations between linguistically-derived protoform-meaning pairings and excavated evidence of material domains of life in historical contexts across periods and around the globe should buoy our confidence in the comparative semantic analysis underlying the reconstruction of the meanings of words for non-material domains of life in contexts without documentary evidence or archaeological support of reconstructed words’ meaning(s).

More than a matter of fact, however, recognizing meaning is a matter of interpreting from among possibilities. These possibilities are socially and contextually, and, therefore, historically contingent. This way of thinking about meaning is central to the historian’s work of interpreting the communicative contents of archives and it is why historians question how we can know what words meant in the past but rarely question how we reconstruct how they sounded. Here, I think, there is a misunderstanding of the scale of the (changes in) meaning recovered through the methods of comparative historical linguistics as opposed to the scales of meaning considered by historians using other archives.

Historians are right to wonder just how these methods can possibly recapture the subtle range of meanings of a word like ‘bird’—the animal category, the prisoner on the lam, the sexualized female target of a (predatory?) male, the single-fingered gesture of insult—at a particular moment in time, particularly in distant pasts.[1] The simple answer is that the comparative historical linguistic method cannot with certainty capture the entire range of meanings of a word in a single language at a particular moment in the past. But, through the comparison of attestations in other genetically or spatially related languages, these methods can recover the core range of a root’s meanings based on those meanings that survived in different conjugations, declensions, and compounds of the root within and across languages (as well as comparison to other words in related lexicons as well as synonyms, antonyms, homophones, and so forth). These methods can also differentiate earlier core meaning(s) from later core meaning(s). Thus, the scale of change is the core semantic range of a root common to a group of languages and innovated by the speech community of their shared protolanguage, not the precise meaning of a word in a specific utterance.

This comparative work is not so very different from the role of comparison in interpreting the meaning of communication recorded in the traditional archive. Historians working with documents trace out the possible meanings of a word through comparisons of uses of that word across many contemporary (or sequential) records to reconstruct a high resolution understanding of how words in a single language carried meaning in different contexts in the pasts they study. This allows historians to recognize atypical uses and, thereby, surprising sentiments. Historical linguists comb through any available iterations (conjugations, declensions, compounds, antonyms, synonyms, related lexis, etc.) across multiple time periods in hundreds of related languages and in the widest range of genres and social contexts, from riddles, to oral histories, to formal dictionaries, to ethnographic observations. These data allow us to reconstruct a much larger scale, lower resolution understanding of how people from different regions in the same time period or the same region over long spans of time made use of similar collections of sounds (roots) to invoke a related core of understanding but not necessarily identical meanings over time and space. Practitioners “argue, in effect, that a word has a minimum representation at the core of its meaning, knowable without context. People do not create the world anew each time they talk. They create it through countless conversations over time” (Schoenbrun 2021:22).

Historians using traditional archives focus primarily (but not exclusively) on statements that can be attributed at the scale of an individual or a subgroup like a jury, national assembly, editorial board, or athletic club. The evidence of comparative historical linguistics records the terms known to the wide community of speakers of a language or protolanguage. Speech communities had their own politics, to be sure, but for the pasts of oral societies, we cannot study such politicking through individual utterances comprising debate. Instead, we need to rely on contestable categories like ‘master’ and ‘slave’ or ‘woman’ and ‘man’ or pay attention to the way that the same root might express contradictory meanings through different morphological configurations or in different social contexts or across language boundaries. Historical linguistic evidence of named categories is, thus, a form of conceptual history (Fleisch and Stephens 2016).

The layers of meaning speakers attached to words over time, their contexts of use, and the many inflections of common roots in a variety of conjugations and declensions inform us as to how inherited terms were kept relevant in changing historical circumstances. Yet, our standards of “knowability” are different in differently-documented contexts (for example, we accept a level of uncertainty in work on the Merovingians than would be unacceptable in work on modern France). Comparative historical linguistic methods necessarily afford the same power to the contingencies of understanding that characterize day to day speech—if not always the confident authority of scholarly writing—because they yield histories of conceptual possibilities, of the fundamental ideas and understandings shaping and shaped by speakers’ actions and circumstances, rather than histories of events or individual acts of communication and meaning-making. These methods offer an opportunity to learn history through the very medium through which it circulated for the oral communities whose pasts we seek and an opportunity to reconcile those understandings with disciplinary practices that emerged from a historical culture of knowledge production that isolated and froze events, interpretations, and understandings in time through the written materials we subsequently approach as archives.

4

Where do I look to learn more about or to use this archive?

Although common practice among Africanist historians, it is not necessary to produce a classification and reconstruct the diachronic phonology of a language family or even produce word reconstructions to use linguistic evidence to write history. But, it helps to know where to find specialists’ classifications and analysis of diachronic phonology, morphology, lexis, and so forth. Like any field, linguists’ scholarship involves contradiction and debate; conclusions change as new information come to light (particularly through field research and language documentation). Language is, therefore, an unstable archive and it likewise has its biases. The concentration of historical linguistic work on Bantu languages far exceeds that on other Niger-Congo branches, creating an imbalance in the field that is reflected in the bibliography of this online resource. Of particular interest to historians of the Atlantic are the wide-ranging findings of linguist Koen Bostoen’s major ERC-funded projects, KongoKing and BantuFirst, which are generating high-resolution technical diachronic analysis of west central African languages at BantUGent. Beyond such high profile projects, historians can look to the following resources to access the technical data supporting efforts to use linguistic evidence in the Atlantic:

Select Specialist Journals, Publishers, and Series

Journals

(excluding those general to Linguistics)

Africana Linguistica

Contemporary African Linguistics

Journal of African Languages and Linguistics

Journal of West African Languages

Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies

Studies in African Linguistics

Presses & Series

Peeters Publishers (Leuven)

-Langue et Littératures de l’Afrique Noire

Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (Tokyo)

-Bantu Vocabulary Series

Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale (Tervuren, Belgium)

-including the Tervuren Series for African Language Documentation and Description

Language Science Press (Berlin, Germany)

-incluging the African Language Grammars and Dictionaries Series

LINCOM GmbH (Munich, Germany)

-including the LINCOM Studies in African Linguistics

Rüdiger Köppe Verlag (Cologne, Germany)

-including numerous series dedicated to African linguistics

Routledge (taking up the series once published by the International African Institute)

-Linguistic Surveys of Africa Series

Major Institutes, Databases & Initiatives focused on African Historical Linguistics

(excluding the programs, institutes, and centers focused on African languages or linguistics more generally)

Culture and Society and Heritage Studies Services, Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale (Tervuren, Belgium)

-including Bantu Lexical Reconstructions-3 (BLR3)

Comparative Bantu Online Dictionary (CBOLD)

UGent Centre for Bantu Studies (BantUGent)

Niger-Congo Reconstruction at LLACAN

5

Bibliography

Works Cited

Bastin, Yvonne, André Coupez, Evariste Mumba, and Thilo C. Schadeberg (eds). 2002. “Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 3 / Reconstructions lexicales bantoues 3.” Last modified November 6, 2005. http://linguistics.africamuseum.be/BLR3.html

Brown, Ras Michael. 2012. African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, Lyle. 2004. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Edinburgh University Press.

de Luna, Kathryn. 2016. Collecting Food, Cultivating People: Subsistence and Society in Central Africa. New Haven: Yale.

de Luna, Kathryn. 2021. “Sounding the African Atlantic.” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. 78 (4): ###-###.

Fleisch, Axel. 2016. “Conceptual Continuities: About ‘Work’ in Nguni.” In Doing Conceptual History in Africa, edited by Axel Fleisch and Rhiannon Stephens, 49-72. New York: Berghahn.

Fleisch, Axel and Rhiannon Stephens, eds. 2016. Doing Conceptual History in Africa. New York: Berghahn.

Fowler, Dennis. 2000. A Dictionary of Ila Usage. Münster, Hamburg, London: Lit.

Geggus, David. 1993. “Haitian Voodoo in the Eighteenth Century: Language, Culture, Resistance,” Jahrbuch für Geschichte von Staat, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Lateinamerikas 28: 32-33.

Ginzberg, Carlo. 2013 [1986]. Clues, Myths and the Historical Method. 2nd ed. Trans. John and Anne Tedeschi. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Mobley, Christina. 2015. “Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery and Culture from Mayombe to Haiti.” Ph.D. thesis. Duke University.

Pokorny, Julius. 1959. Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Bern: Francke. [this three-volume resource is digitized in various forms and is freely available online].

Schoenbrun, David. 2021. Names of the Python: Belonging in East Africa, 900-1930. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Slocum, Jonathan and UT Austin Linguistics Research Center. n.d. “Indo-European Lexicon.” Accessed June 28, 2021. https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/lex.

Stephens, Rhiannon. 2016. ‘Wealth’, ‘Poverty’ and the Question of Conceptual History in Oral Contexts.” In Doing Conceptual History in Africa, edited by Axel Fleisch and Rhiannon Stephens, 21-48. New York: Berghahn.

Thornton, John. 1993. “‘I am the Subject of the King of Kongo’: African Political Ideology and the Haitian Revolution,” Journal of World History 4 (2): 181-214.

Watkins, Calvert. 2000. The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. 3rd. ed. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

General Introductions to the Method & Relevant Language Families

Bendor-Samuel, John (ed.). 1989. The Niger-Congo Languages. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Bostoen, Koen. 2017. “Historical Linguistics.” In Field Manual for African Archaeology, edited by Alexander Livingstone Smith, Els Cornelissen, Olivier Gosselain, and Scott MacEachern, 257-60. Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa.

Bostoen, Koen and Yvonne Bastin. 2016. “Bantu Lexical Reconstruction.” Oxford Handbooks Online. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.36

Campbell, Lyle. 2004. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Edinburgh University Press.

Crowly, Terry and Claire Bowern. 2010. An Introduction to Historical Linguistics, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

de Luna, Kathryn and Jeffrey Fleisher. 2019. Speaking with Substance: Methods of Language and Materials in African History. New York: Springer.

Dimmendaal, Gerrit. 2011. Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ehret, Christopher. 2010. History and the Testimony of Language. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hale, Mark. 2007. Historical Linguistics: Theory and Method. Hoboken: Blackwell.

Hock, Hans Henrich and Brian Joseph. 2009. Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An introduction to historical and comparative linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Millar, Robert McColl, ed. 2015. Trask’s Historical Linguistics, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

Nurse, Derek. 1997. “The Contributions of Linguistics to the Study of History in Africa. Journal of African History, 38 (3): 359-91.

Nurse, Derek and Gérard Philippson. 2003. The Bantu Languages. New York: Routledge.

Ringe, Don and Joseph Eska. 2013. Historical Linguistics: Toward a Twenty-First Century Reintegration. New York: Cambridge.

Weiss, Michael. 2014. “The Comparative Method.” In The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, edited by Claire Bowern and Bethwyn Evans, 127-146. London: Routledge.

Semantic Reconstruction & ‘Meaning’

Bastin, Yvonne. 1985. Les relations sémantiques dans les langues bantoues. Brussels: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer.

Bostoen, Koen. 2005a. “A diachronic onomasiological approach to early Bantu oil palm vocabulary.” Studies in African Linguistics 34 (2): 143–188

Bostoen, Koen. 2009. “Semantic Vagueness and Cross-Linguistic Lexical Fragmentation in Bantu: Impeding Factors for Linguistic Paleontology.” Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 20: 51-64.

Evans, Vyvyan. 2009. How Words Mean: Lexical Concepts, Cognitive Models, and Meaning Construction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fleisch, Axel. “The Reconstruction of Lexical Semantics in Bantu.” Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 19: 67-106.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 1997. Diachronic Prototype Semantics: A Contribution to Historical Lexicology. Oxford: Clarendon.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 2010. Theories of Lexical Semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hanks, William. 1996. Language and Communicative Practices. Boulder: Westview Press.

Hanks, William. 2010. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schoenbrun, David L. 2019. “Words, Things, and Meaning: Linguistics as a Tool for Historical Reconstruction.” In The Oxford Handbook of African Languages, edited by Rainer Vossen and Gerrit Dimmendaal, 961-72. New York: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199609895.013.85

Schoenbrun, David L. 2019. “Early African Pasts: Sources, Interpretations, and Meaning.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Historiography: Methods and Sources, Vol. 1, edited by Tom Spear, Kathryn M. de Luna, Peter Limb, Peter Mitchell, Richard Waller, Olufemi Vaughan, 7-44. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stephens, Rhiannon. 2016. ‘Wealth’, ‘Poverty’ and the Question of Conceptual History in Oral Contexts.” In Doing Conceptual History in Africa, edited by Axel Fleisch and Rhiannon Stephens, 21-48. New York: Berghahn.

Wilkins, David P. 1996. “Natural tendencies of semantic change and the search for cognates.” In The Comparative Method reviewed: Regularity and irregularity in language change, edited by Mark Durie and Malcolm Ross, 264-304. New York: Oxford University Press.

Major Databases and Compendia of Cognate and Proposed Reconstructions

Bastin, Yvonne, André Coupez, Evariste Mumba, and Thilo C. Schadeberg (eds). 2002. “Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 3 / Reconstructions lexicales bantoues 3.” Last modified November 6, 2005. http://linguistics.africamuseum.be/BLR3.html [often cited as ‘BLR-3’]

Bourquin, W. 1923. Neue Ur-Bantu-Worstämmen nebst einem Beitrag zur Erforschung der Bantuwurzeln. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

Bourquin, W. 1953. “Weitere Ur-Bantu Worstämme,” Afrika und Übersee 38: 17-48.

Crabb, D. W. 1965. Ekoid Bantu languages of Ogoja, Eastern Nigeria. Cambridge University Press.

“CBOLD: Comparative Bantu Online Dictionary.” Accessed June 28, 2021. http://www.cbold.ish-lyon.cnrs.fr/

Elugbe, B.O. 1989. Comparative Edoid: phonology and lexicon. Port Harcourt: University of Port Harcourt Press.

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1967-1971. Comparative Bantu, 4 vols. Farnborough: Gregg.

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. The Languages of Africa. The Hague: Mouton.

Meeussen, Achille Emiel. 1980. Bantu lexical reconstructions (Reprint). Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa)

Ohiri-Aniche, C. 1991. A reconstruction of Proto- Igboid-Yoruboid-Edoid. Ph.D., University of Port Harcourt.

Schoenbrun, David Lee. 1997. The historical reconstruction of Great Lakes Bantu: etymologies and distributions. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Westermann, D. 1927. Die Westlichen Sudansprachen und ihre Beziehungen zum Bantu. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Williamson, K., and K. Shimizu. 1968. Benue-Congo comparative wordlist, Vol. 1. Ibadan: West African Linguistic Society.

Williamson, Kay 1973. Benue-Congo comparative wordlist: Vol.2. Ibadan: West African Linguistic Society.

Wolff, H. 1969. A comparative vocabulary of Abuan dialects. Evanston: North-Western University Press.

6

How to cite this material: de Luna, Kathryn M. “Methods.” Atlantic Language Archive. Georgetown University. [Insert Access Date Here]. http://atlanticlangarchive.georgetown.edu/methods/.